“What is the impact of having the ownership names/signatures in books?” was a question directed my way yesterday by a woman, who with her husband, has just arrived from Ontario with some books for me to look at. “It depends” I answered. Most of the books they had brought to me had a previous owner’s name in almost everyone. That was about the extent of the conversation. More about this later. I bought about half of the books. Today, I entered the books into inventory and all day I was thinking about the dilemma of ownership names in books – hence this musing.

Note, that I am focusing on the written word and not ownership reflected by the presence of bookplates – a whole different animal.

Let me start by looking at the extremes.

The collectors of modern literary first editions focus on the pristine nature of the book and of the dust jacket. An otherwise $100 book lacking the dust jacket becomes a $20 book and would be shunned by collectors. If I had written my name inside that book, the result is almost the same. Even the name of a well-known person is a problem.

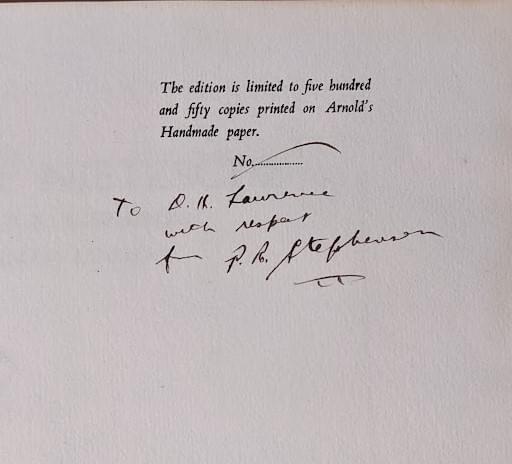

The other extreme is where the name of a well-known personage has scrawled their name inside a book and, of course, is not the author. Typically, where the owner is deceased, and has been for a generation or two. Sometimes, the owner has not written their name in the book, but the author has presented the book to the owner. It is unusual where the recipient is more notable than the author. And there has to be evidence that the owner has received and accepted the book into his or her library and has, perhaps, been impactful. For instance, if an author has signed a book with a presentation to Ernest Hemingway there would have to be proof that Hemingway did, indeed, receive the book with open and welcoming arms.

Here are two examples from Raven & Gryphon Fine Books.

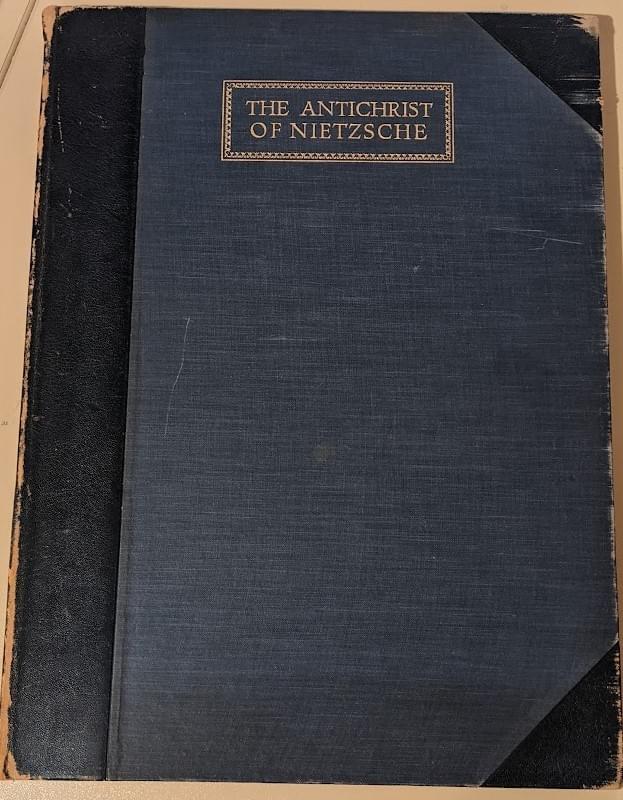

The Antichrist of Nietzsche: A New Version in English by P. R. Stephensen; with illustrations by Norman Lindsay; The Fanfrolico Press, London, 1928.

I have two copies of this book for sale. One is priced at $800, and the other is priced at $4,000, the difference obvious from the photo.

These books were transferred from my personal collection. I already had the former volume and when I had the opportunity to but the latter volume I did not hesitate. Here is part of the description covering the more expensive book in our listing on the internet.

“From the Book Wild Man of Letters: The Story of P. R. Stephensen, by Craig Munro, Melbourne University Press, 1984 – At this time Lawrence was in a fury over the English suppression of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. So, he eagerly seized upon the possibility of publishing his paintings, a project Jack Lindsay had suggested in an offhand way to Orioli. Lawrence not only asked Davies to mention it to Stephensen, but on 14 December wrote to his London friend, S. S. Koteliansky, enclosing a letter to Lindsay offering an introductory essay on modern painting if the Fanfrolico would issue his paintings. Before Lawrence’s letter reached England, Stephensen arrived in France with his trunk of books, putting up in fashionable Nice where he had little difficulty disposing of his expensive stock. Rhys Davies was also in Nice, and a week before Christmas 1928 Stephensen decided to travel down to Bandol with him by train, a journey of some hours, to visit Lawrence. They spent two days with Lawrence and Freida at the Hotel Beau Rivage and Stephensen dropped Winifred a line on hotel notepaper saying he had got on wonderfully with Lawrence. Stephensen also presented several Fanfrolico books – including this book – to Lawrence who afterwards characterized them to Huxley as what a waste of good printing. But Stephensen assured Lawrence that the paintings would be published under a new imprint, and one which would not employ any of Norman Lindsay’s artwork, for which Lawrence obviously had scant respect. The new press, which Stephensen called the Mandrake, had already been discussed with Jack Lindsay and was tentatively planned as an offshoot of the Fanfrolico. That did not happen and Stephensen left Fanfrolico and set up the Mandrake Press, where he published Lawrence and Aleister Crowley.”

It would appear that Lawrence had printed his name at the top of the page in the photo. This meeting and presentation of the books had a significant impact on both of their lives with the recipient of the book much more important in the collectors’ market than the author.

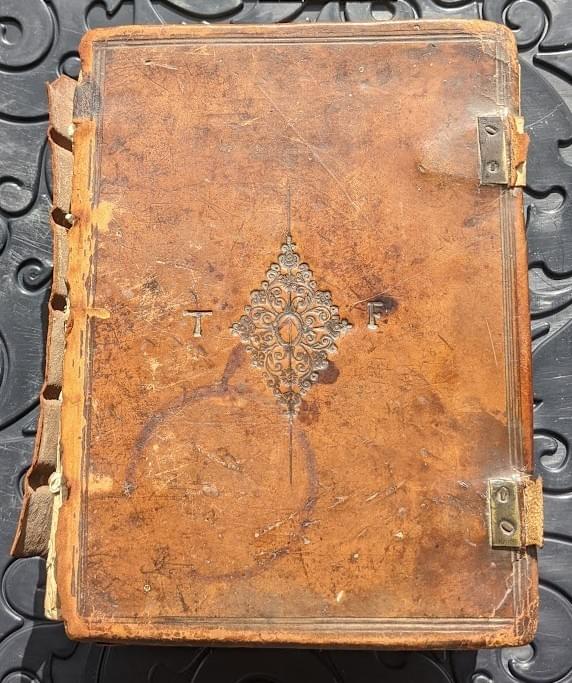

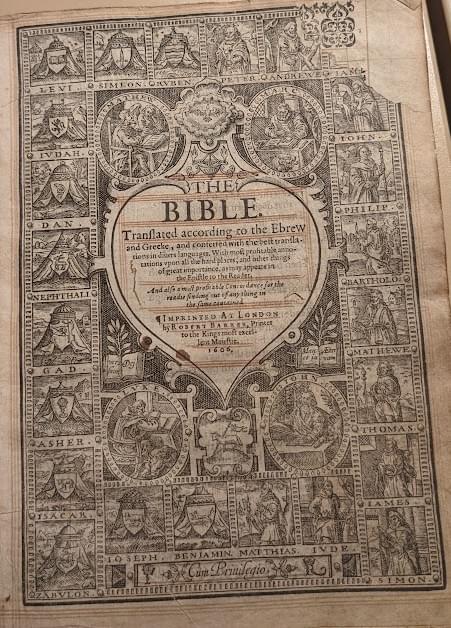

The Bible, imprinted in London by Robert Barker, printer to the King most excellent Majistie, 1606.

We acquired this book in the spring, and it is now in Ontario being cleaned and reattaching the front cover.

This is the Breeches Bible, so named because when Adam and Eve sinned and realized that they were naked they took fig leaves and made themselves ‘breeches”. This book was adopted by the Puritans.

Look closely at the photo of the cover of the book – you can see the initials “T” and “F”. A mystery until I saw on the last page in the book, a page frail and only 70% there, the signature of the owner, Thomas Fell. Unfortunately, I did not take a photo of that page before I sent it off to be rebound.

To my surprise and delight Thomas Fell had his own Wikipedia page and here is some of what it says.

“Thomas Fell (1598 – 8 October 1658), was a lawyer, member of parliament and vice-chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. In 1645, he was elected to parliament for the city of Lancaster. In the following year, on the newly remoulded section of the local church, his name appears on the list of laymen for the presbytery of Furness. In 1648, Oliver Cromwell named him a commissioner for the safety of the county, and in 1649 he was nominated vice chancellor of the duchy and attorney for the county palatine. From 1650 to 1651, he was chosen as bencher of Gray's Inn, and is recorded as being at that time a judge of assize for the Chester and North Wales circuit.

Fell was considered a leading puritan in the district of Furness, and practised hospitality

with his wife's assistance. During his absence on circuit in 1652, the family was converted by George Fox. Fell hastened home and was met by Fox, who explained his doctrines. Although Fell never embraced Quakerism, he granted the use of Swarthmoor Hall for friends to meet in, and frequently sat in an adjoining room with the door open, so as to afford them the protection of his presence. His wife said, "He was very loving to Friends."

This book will be marketed as “The Thomas Fell” copy probably at $6,000. Without the Fell connection $4,000.

Generally, I find that the older the book, contemporary ownership signatures provide an element of provenance.

History of Merioneth; Volume 1 – from the earliest times to the Age of the Native Princes; by E. G. Bowen and C. A. Gresham; The Merioneth Historical and Record Society, Dolgellau, 1967. Printed in Wales by J. D. Lewis and Sons Limited, at the Gomerian Press, Llandysul, in the County of Gardigan, MCMLXVII.

The book had the contemporary ownership signature on the first free endpaper of a Mr. Jones in Llanrwst, a village located in Merioneth. (No photo, sorry)

This book has been sold and returned to Wales, and I believe that the new owner noted the ownership provenance.

Other examples where the ownership name is of interest is where that person was part of the story, often seen in military or travel journals.

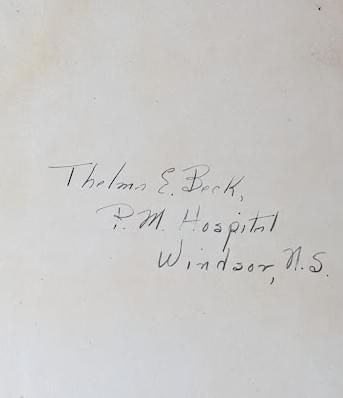

The Care of Tuberculosis, by J. A. Myers, Ph.D., M. D.; W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1924.

As you can see from the photo, the owner was a health care worker – part of the story.

In these last two examples, the presence of the signature did not increase the price of the book. The signatures did not decrease the price either but rather makes these books more attractive to the buyer. As a book dealer, I believe this makes the volumes easier to sell, and therefore, I would often pay a bit more for this saleability feature.

Now, let’s return to yesterday’s purchase. I discovered today that the owner of these books was both a Nova Scotian author and a book collector and lived in Bridgewater.

Some of the books were presented to him by Nova Scotia writers, not as well known today as the recipient. Doesn’t add to the price or value but makes the books more attractive to potential buyers, especially, if they too are Nova Scotian.